The hopes of Makali and Lina Kilii lie parched and withered beside their huts. It is early summer in the small Kenyan village of Kinakoni, usually a time of lush greenery and ample growth.

In normal times, the “long rains” – the season of heavy rainfall in Kenya – are just about over. Three months of torrential rain drench the red earth, allowing maize, millet and beans to flourish, enough to tide the family over in the difficult months ahead. In normal times.

But here in Kinakoni, nothing has been normal for a very long time.

There have only been very few showers at all this rainy season. Kilii leads the way across the field next to the huts. Almost every family here has a “shamba” like his, as the small field is called in Swahili. It is a rectangle measuring maybe 50 by 100 metres. And the sounds underfoot are similar on all of them: there is a crackling noise as the dried leaves of the plants rustle in the wind.

None of the maize plants will produce a single cob. What about the millet? No chance! A few meagre beans have survived and trickle into his hand from shrivelled pods. “It’s getting harder every year”, says Kilii, “you can’t feed a family on that.”

Experts agree that the withered field belonging to the couple is the result of climate change. The rains in East Africa, in particular, are becoming more unpredictable, the harvests more difficult – one of the reasons for a disastrous development being witnessed in several parts of the world: the hunger crisis is back.

The ghosts are returning

This trend is as astonishing as it is frightening. For a long time, humankind was well on the way to making hunger a scourge of yesteryear. The bloated bellies of children from the Nigerian region of Biafra in the 1960s or from the Ethiopian territories ravaged by civil war in the 1970s and 1980s seemed to be ghosts from the past.

But now these ghosts are returning. While the number of malnourished people declined steadily until around 2014, this decrease has stalled considerably and is now showing a reverse trend, partly also due to the loss of income as a result of the pandemic. This year, some 270 million people are facing food shortages – almost double the number compared to pre-Corona levels. And more than 40 million people are on the verge of a famine. “I’ve never seen the world face a situation as bad as this”, says Amer Daoudi, Senior Director of Operations at the World Food Programme (WFP), the food-assistance branch of the United Nations.

Once again, Africa is the continent most strongly affected. If it comes to the worst, several hundred thousand people in the embattled Ethiopian province of Tigray could starve to death; and the situation in southern Madagascar has reached dramatic proportions after an unprecedented drought. But even stable countries like Kenya are once again struggling with hunger. Currently, 20 per cent of the people on the African continent are considered undernourished. By 2030, the United Nations predicts this figure will increase to 25 per cent.

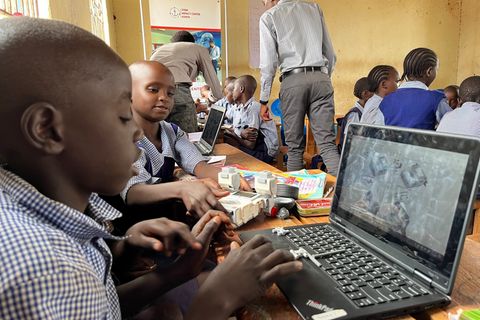

And yet, contrary to the common cliché, many African countries have experienced quite stunning developments since the turn of the millenium. Cities like Lagos, Kigali or Nairobi have become startup hubs, with coworking offices that look no different from those in Berlin, except that the men and women with to-go coffees in their hands and headsets over their ears are black. Even in the Corona-year 2020, 1.3 billion US dollars of venture capital was invested in the continent.

How does that fit together – economic awakening and hunger? And could one possibly provide the solution to the other?

Stern and Deutsche Welthungerhilfe, the German non-governmental World Hunger Relief agency, are examining this question within the framework of a unique project. Over a period of three years, we want to investigate the reasons for this acute food insecurity using the village of Kinakoni as an example, and, together with the inhabitants, develop measures to combat this hunger emergency in the long term.

The most important point, however, is that not we as Germans from faraway Europe will be the ones to tell them how things should be done. The aim is to find answers to the problems in Kinakoni with the help of founders from the startups in Nairobi and to then implement these solutions in other villages. Also on board is the Frankfurt-based venture capital firm GreenTec Capital, which has good contacts in the startup scene of the Kenyan capital.

We want to take you with us on our journey and give you an opportunity to meet the inhabitants of Kinakoni, hear their stories, listen to their problems and learn about their hopes and aspirations. Get to know the project village where it all began on a Wednesday in late June this year.

On this particular day, some 50 residents from Kinakoni gather in the shade of a few acacia trees right next to a big rock. They have assembled to discuss the upcoming project with a team from stern and the Welthungerhilfe and to talk about the problems and opportunities facing their homeland.

Kinakoni lies 250 kilometres to the south-east of Nairobi in the midst of a vast plain. Getting there involves first driving along multi-lane highways and then over dusty dirt roads. It is an arid Savanna landscape, very reminiscent of a picture-book Africa.

Acacias, baobabs and shrubs grow in between the families’ huts and fields, and a partially dried-up stream meanders through the plain. Around 5000 people live here. Kinakoni is dominated by several high hills from where you can see dozens of kilometres into the distance until the view is lost in the haze.

The villagers draw their home into the earth, using colours, leaves and fallen fruit to pinpoint the schools, the market and the streets – all with the aim of highlighting the problems.

It is a lively discussion. The men and women delegated by the village community stand together, sometimes in groups, sometimes in a semicircle around the village map while the moderator of the workshop summarises their thoughts and ideas on a presentation board.

Makali Kilii, the farmer with the dried-up field, has also come. Kilii is a quiet man who stays in the background although he has the same problem as almost everyone here: He barely knows how to feed his family.

Makali Kilii, aged 46, and his wife Lina, aged 40, have seven children. The youngest is five and the oldest 21 years of age – she already has a baby of her own. They all live in several huts made of mud bricks in the middle of Kinakoni. A few scrawny chickens and stray dogs run around between the huts; scraps of plastic bags are entangled in the bushes; a pile of rocks is strewn under a tree, next to which lies a moped pedal: it is with this improvised hammer that Lina Kilii crushes the larger chunks of rock into gravel, thus providing the family with at least some meagre income.

Life in Kinakoni has never been easy. The landscape is barren, there are hardly any jobs, and most people live from hand to mouth. The past has also seen its share of famines. And yet the climate was more predictable. In good years, the Kilii family earned extra money by selling vegetables they had grown in their field. In normal years, the yield was sufficient to feed all the family members. But what of the bad years that are becoming more and more frequent?

“We only eat once a day, in the evening. In the morning we only have tea. Nothing at noon”, says Kilii. What he describes is what food security experts call coping strategies. Skipping meals is always one of them. In addition to that, if the food is very one-sided – in the case of the residents of Kinakoni, this is often ugali, a maize porridge – it has a rapid and detrimental effect on physical and mental performance. Hunger is a tenacious intruder. Once it has taken hold of the body, it rages there for a long time, even when sufficient food is once again available. “Hunger affects practically all organs. If anything, the question should be: Is there a part of the body not ravaged by hunger?”, says Michael Krawinkel. The paediatrician and former professor for human nutrition at the University of Giessen is an authority on malnutrition and an advisor to the Welthungerhilfe.

A lack of protein, for example, means that fats in the heart muscle can no longer be mobilised and used for energy production. Instead, too much fat is deposited in the heart muscle cells, which is one of the reasons why malnourished children often develop heart failure.

As it is, the youngest suffer the most: their bodies are growing and need more nutrients per kilo of their own weight. And once their liver has been damaged by hunger, their bones no longer develop properly either.

Half of the children in Kitui County are affected by stunting

Researchers call this reduced growth rate due to malnutrition “stunting”. The afflicted children often remain years behind their peers. Here in Kinakoni, it is noticeable how small many of the children are – and this impression is borne out by statistics: In some areas of Kitui County, almost half of the children are affected by stunting.

If hunger slows down children’s growth spurts during puberty, then they remain stunted and of shorter stature throughout their adult lives. “In the past, stunting was trivialised as simply being an adaptation process of the body to lean times”, says the paediatrician Krawinkel. “But today we know that children suffering from stunting also have a higher mortality.”

Makali and Lina Kilii have also lost a child. Jonas, who was born in 1997, died after only four months. The exact reason for his death is unclear. His parents say he was weak. The other children in the family seem small, too small for their age. And here, too, the cause is likely to be stunting.

Feeding a family from the yields of their field has never been easy in Kinakoni, “but in the past the rains were more reliable”, says Kilii. He sits in the shade in front of one of his huts, the older children at his feet. They listen to their father talking about his childhood, but to them it sounds like something out of a fairytale.

“We sowed when the first rains fell in March. The plants simply grew. We didn’t have to do much.”

The extreme shift in the rhythm of wet and dry seasons is one of the reasons for the return of hunger in East Africa. Normally, two harvests would be possible here. One in July and August, and another in January and February, in each case following the rainy seasons.

However, the current crop is almost entirely lost, and the forecast for the next one hardly looks any better. Meteorologists predict a prolonged drought, which is why Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, declared a state of emergency at the beginning of September. In the hardest hit areas in the north of the country and in Tana River county, the herds belonging to the nomads are already dying. East Africa has always been hit by droughts, but unlike a few decades ago, they now follow each other in ever quicker succession.

It is not only the lack of rain that is affecting people. For two years, the region has been devastated by huge swarms of locusts. Behind this phenomenon lies a chain reaction that began in 2018 when the Arabian Peninsula experienced unusually heavy rainfall, allowing swarms of these voracious insects to develop and be carried across to Africa with the winds. According to experts, the underlying cause of this rainfall in the desert is, once again, climate change.

The consequences of the pandemic

On top of this, the lockdown during the Corona pandemic caused incomes in many families to plummet. The vaccination rate in Kenya is dramatically low due to the lack of vaccines; less than three per cent of the population have been inoculated. The consequences are evident in the poorer districts of the cities but also in rural areas like Kinakoni. Many families here rely financially on a father, uncle or a brother who works in Nairobi or Mombasa as a bricklayer or a day labourer or in the kitchens of restaurants or hotels. But now, these breadwinners are no longer able to send money and instead require financial assistance themselves.

Josephine Mbuvi, who as village administrator is in charge of Kinakoni, tells us that for months she has had to send money to her husband, a construction worker in the coastal town of Malindi. Actually, it should have been the other way around.

Mbuvi, age 40, is one of the men and women from Kinakoni we want to accompany over the next three years. She is an impressive self-made woman who has managed to work her way up to the position of mayor – and yet she can barely pay for food for her children.

Kavata Katithi is Malaki and Lina Kilii’s neighbour. The 36-year-old has to raise three children on her own – not an unusual fate. Time and again, men abandon women as soon as they become pregnant; family planning with contraceptives is almost non-existent. Katithi works six days a week in a small butcher’s shop at the Kinakoni market. She earns about two euros a day, barely enough to support her family. To make matters worse, Duncan, her eldest son aged 14, suffers from a developmental disability, but Katithi lacks the money to send him to a suitable school.

Peter Mulwa is a beekeeper like his father and grandfather before him. Around 20 men in Kinakoni earn their living keeping bees. Three times a year, Mulwa hangs hollowed-out pieces of tree trunks in the acacia trees as hives for the insects. After several weeks, he harvests the honey in a hair-raising night-time operation and without a protective suit. Thanks to the acacias, the honey has an intense and spicy taste. But Mulwa does not earn much money with his bees. Most of it goes to the middlemen.

Jeremiah Mbai wrestles with other worries. He is 19 years old and attends the final year of secondary school in Kinakoni – if and when he can go. Oftentimes, Jeremiah is not allowed to attend classes because his mother cannot afford the fees. He has been forced to repeat the eighth grade, the last year of primary school – not due to poor performance but through lack of funds. His two older brothers were already at the more expensive secondary school, but his mother was unable to afford the tuition for all three. The tragedy is that Jeremiah is by far the best in his class.

Given the fact that various governments, development agencies and relief organisations have been grappling with this predicament for decades, stern and Welthungerhilfe are not so presumptuous as to imagine they can solve all these issues with the help of startups from Nairobi. But contrary to the approach usually taken in development cooperation, we have decided to do a few things differently, and we want to regularly allow you to share and participate in our work. Our objective also involves putting the topics of hunger and developmental cooperation back on the agenda. Together, stern and the Welthungerhilfe want to raise awareness and provide more information on methods, approaches and innovations. And we want to clarify that the Africa of 2021 is not the Africa of 1980; and that the problems facing the continent are also offset by opportunities.

Possibly no other city symbolises “the other Africa” better than Kenya’s capital Nairobi – home to the young entrepreneur Anne Nderitu.

The "other" Africa

We meet Nderitu in her company’s office in the centre of Nairobi. Outside, people, cars and taxis throng the streets: the usual chaos of a megacity. Inside, too, the office is a hive of bustling activity: cables and tools lie alongside laptops, the conference table doubles as a workbench. On top of it lies a two-metre-long aircraft made of wood, plastic and electronics. It is a drone that was developed by Nderitu’s team.

Nderitu, aged 26, has attentive eyes and a winning smile. She is one of the three founders of Swift Lab, a Kenyan startup that uses these flying objects to measure fields and transport medicines.

Catastrophes, conflicts and crises – that is the triad many still associate with this continent. And it is not entirely wrong, as the example of Kinakoni shows. But there is also the other Africa. Cities like Nairobi are home to a young urban elite who, much like their peers in Europe, Asia and America, order their Uber taxis or food via an app; or struggle with a pitch to their financier instead of harvesting crops in a maize field.

“I get incredibly annoyed when I hear the clichés circulating about Africa”, says Nderitu, the young entrepreneur. “As if all the women here were constantly walking around balancing pails of water on their heads!”

In Kenya, the digital revolution began about 15 years ago. Ushahidi, a platform developed by local programmers, helped document assaults against opposition members after the 2007 presidential election. Almost at the same time, M-Pesa was launched onto the market, a mobile-phone based payment system. Today, you can use it to buy a coke at any kiosk, even in the slums.

Nderitu currently employs nine men and women in her company, with that figure set to increase soon. Drones are considered the industry of the future in Africa. They can be used to transport small loads at low cost, notably in areas where there are hardly any roads.

At present, the company makes most of its revenue with agricultural and mapping contracts. Local authorities, for example, book the Swift-Lab team to locate areas that are particularly at risk from cholera. From the air, it is easier to pinpoint tracts where polluted water collects and cholera bacteria might develop. The mini aerial vehicles can also distribute pesticides, which is cheaper and safer than having workers handle the toxic agents.

Anne Nderitu acquired a flying licence for smaller helicopter drones at an academy in Malawi. Upon her return to Kenya, she also received her licence for large winged drones – the first woman in Kenya to do so.

Along with ideas put forward by other founders, drones from Nderitu’s company will now be deployed in Kinakoni. Among other things, they are designed to help find the best areas for planting fruit and vegetables.

But the first order of the day is something entirely different: water. For that is precisely what Makali Kilii, Kavatha Katithi and the other villagers attending the workshop in Kinakoni determined as their most pressing problem. After three days of discussing, collecting and rejecting proposals, “water” topped the list of priorities. Ahead of health, education and jobs.

So the first goal of our project will be to improve the supply of water. The reservoirs in the rocks surrounding Kinakoni, where water is collected during the rainy season, will play an important role. In order to provide better storage for this water during the dry season, tanks are currently being built down in the plain, with the active help of the villagers.

These tanks are the foundation for everything that is to follow, and they are being built based on the experience the Welthungerhilfe team has gained in terms of water provision in other areas.

For that is precisely what the Kinakoni project is all about: exchanging experiences, daring to try something new and doing it in conjunction with the people it affects.

Not everything will work out. Nevertheless, we are convinced that many things will. As yet, nobody knows the exact route this journey will take, but the cause makes the journey worthwhile. Join in, and accompany us and the people from Kinakoni.