.

May 1, 2023, should have marked a new beginning for Magdalena Mucutuy, from the Witoto people, and her four children. A few days before, they had left their Amazon village of Puerto Zábalo by boat and on this cloudy Monday morning, they are on their way to Bogotá, Colombia's capital. Mucutuy wants to join her husband Manuel Ranoque, who had fled two weeks earlier.

Both had recently been forced to work as marijuana couriers for the mafia while paying protection money to the guerrillas – a not uncommon circumstance in this remote part of Colombia. They were also afraid that their eldest daughter Lesly, 13, might become a victim of forced recruitment by the guerrillas – another common danger in this lawless area.

Thus, after more than 30 years in the Amazon, the parents leave everything behind. Their hut, the corn and cassava fields, and their beloved rainforest, which has taught them so much: how to fish and hunt, which wild plants and seeds are edible, the spirituality of each tree, and fear of the "duendes," the spirits of the forest.

At 6:20 a.m. Mucutuy, 34, and her children board a charter plane in Araracuara, the nearest town with an airstrip. The charter company, Avianline, has had engine problems in the past. The family wants first to fly to San José del Guaviare, 350 kilometers to the north, a city that is connected to the road network. Little Cristin, just eleven months old, sits on Magdalena's lap. Next to her is Tien, her only son, who will turn five in a week. Behind them, in cushioned leather seats, daughters Soleiny, 9, and Lesly, 13, both calm and well-fed, a fact that will come in handy later.

Then, at 6:42 a.m., their flight takes off. The start of a new life.

***

750 kilometers away, in Bogotá's suburb of Soacha, Manuel Miller Ranoque, 32, has been awake for some time. He sends a final text message to his wife. "Have a good flight, honey." He lives with his sister Luz in a poor neighborhood and has already found a job as a gardener. As a native of the Witoto people who only knows life in the jungle, he finds the nation’s capital overwhelming. "But it is now the place that offers my family protection from organized crime," he says.

Ranoque is a stocky man with broad shoulders, sculpted from countless marches as a courier, carrying heavy bags of marijuana. The interview takes place in late June at a hotel in the Santa Fe neighborhood, where he feels safe from the tabloid media. For two hours he talks about his life, in which nothing is the way it used to be. Over the following days, we meet him several more times, at his sister's house, in the poor neighborhood, at the military hospital where his children recover.

"Talking about it is hard, but it helps me to understand things," he says.

His wife writes to him from the plane at 6:30 a.m. on May 1 – "We are leaving now."

It will be her last message.

***

The first signs of trouble on board the six-seater Cessna U206G come 35 minutes after takeoff from Araracuara. They are almost halfway through their flight over dense, seemingly endless rainforest, when the engine starts sputtering, and the plane drops off the radar. "Mayday, mayday," radioed captain Hernán Murcia, 55, an experienced pilot, to Colombia's Aviation Safety. "The engine failed me again. I’m looking for an emergency landing site. I have here a river to my right," Murcia says, a clue that will later play a role in the search effort. "I will attempt a water landing."

He fails. At about 7:45 a.m., the white propeller plane with the registration number HK2803 crashes almost vertically through the canopy of trees without cutting a swath and nosedives straight into the ground. The engine falls off and lands 20 meters away. The pilot and Magdalena Mucutuy are killed instantly – as a military medical examiner will later determine. The third adult passenger, the indigenous leader Herman Mendoza, also dies instantly. He is decapitated by the forceful impact.

A short time later, news agencies report the crash. It dominates the morning news in Colombia, not least because there were four children on board, including an infant. The news now reaches people whose lives will be upended by it in the coming weeks.

In northern Bogotá, it reaches General Pedro Sánchez, head of the elite CCOES unit, and his best officers Montiel and Rojas, who are busy fighting terrorists. On the banks of the Río Putumayo, the shaman Jorge Rubio and Eliecer Muñoz, the local leader of the Guardia Indígena, a kind of security force for the indigenous communities, hear the news. Both have a premonition that the children may have survived. In the large city of Villavicencio, southeast of Bogotá, the news reaches Magdalena's parents, Narciso Mucutuy and Fátima Valencia, who say a quick prayer. And finally, it reaches Manuel Ranoque, who just at that moment visits the Red Cross to receive help as a displaced person. His sister Luz has called him. "Have you heard? The plane crashed," "Who can survive something like that?"

Ranoque leaves immediately for San José, where his wife and children should have landed. From there, he hopes to reach the crash site. He manages to assemble a group of indigenous people who know the area. With their help and equipped with machetes, he wants to make his way to the scene of the accident. "Is it possible they are all dead?" he keeps asking himself. "They're all I have."

All eight of the main characters in this drama now rush to join the search effort dubbed "Operation Hope" to rescue any possible survivors. They all share their experiences with stern magazine for the reconstruction of the events over these 40 days. All of them use the same word: Milagro. Miracle.

***

The very next day, May 2, President Gustavo Petro orders the Air Force to deploy several reconnaissance aircrafts to the disaster area in southern Colombia. However, they don’t find anything. No wreckage, no conspicuous swath cut through the forest, no damaged trees, not even near the Apaporis River, where they suspect the plane must have crashed.

The military changes its strategy and on May 6 transfers responsibility for "Operation Hope" to General Pedro Sánchez, the highly decorated commander of the special CCOES unit. He stakes out a search area of 430 square kilometers and immediately deploys 40 elite soldiers to the region. "I thought we would find them quickly," he says. "True, I'd never overseen a humanitarian mission like this before. But we had the best technology at our disposal, satellite photos, night vision cameras, thermal optics, searchlights, search dogs."

***

On a Sunday in late June, General Sánchez, 50, sits in Bogotá's Military Club, a palatial residence in the northern part of the capital. With framed pictures of all the generals adorning the walls it looks like an ancestral portrait gallery. Colombia has a long military tradition, not always illustrious. In the long war between state and guerrillas, armed forces have killed many indigenous people. The mistrust that stems from this legacy makes any cooperation difficult - even in the initial phase of the rescue effort for the passengers aboard the missing plane.

Sánchez is a wiry man. Although he has been back from the search area for two weeks, his hands and neck are still covered with mosquito bites. The interview lasts three hours. "It was a historic mission," he says. "Mysticism and spirituality also played a big role."

Sánchez is a hard-nosed guy, but a few times during the conversation his eyes well up. "I kept thinking about my son, 70 percent of my people have children."

The mission turns out to be more difficult than expected. Visibility in the jungle is only 20 meters, sunlight doesn't reach the ground, and it often rains for 16 hours a day. His men must be vigilant for jaguars, snakes, and poisonous plants - and for the guerrillas, the "Disidencia," a Farc splinter group that continues to control large areas of the jungle. It is one of the densest, wettest, least explored corners of the Amazon basin.

"We got a lot of help, satellite imagery from the U.S., Israel, Chile, but we didn’t find anything."

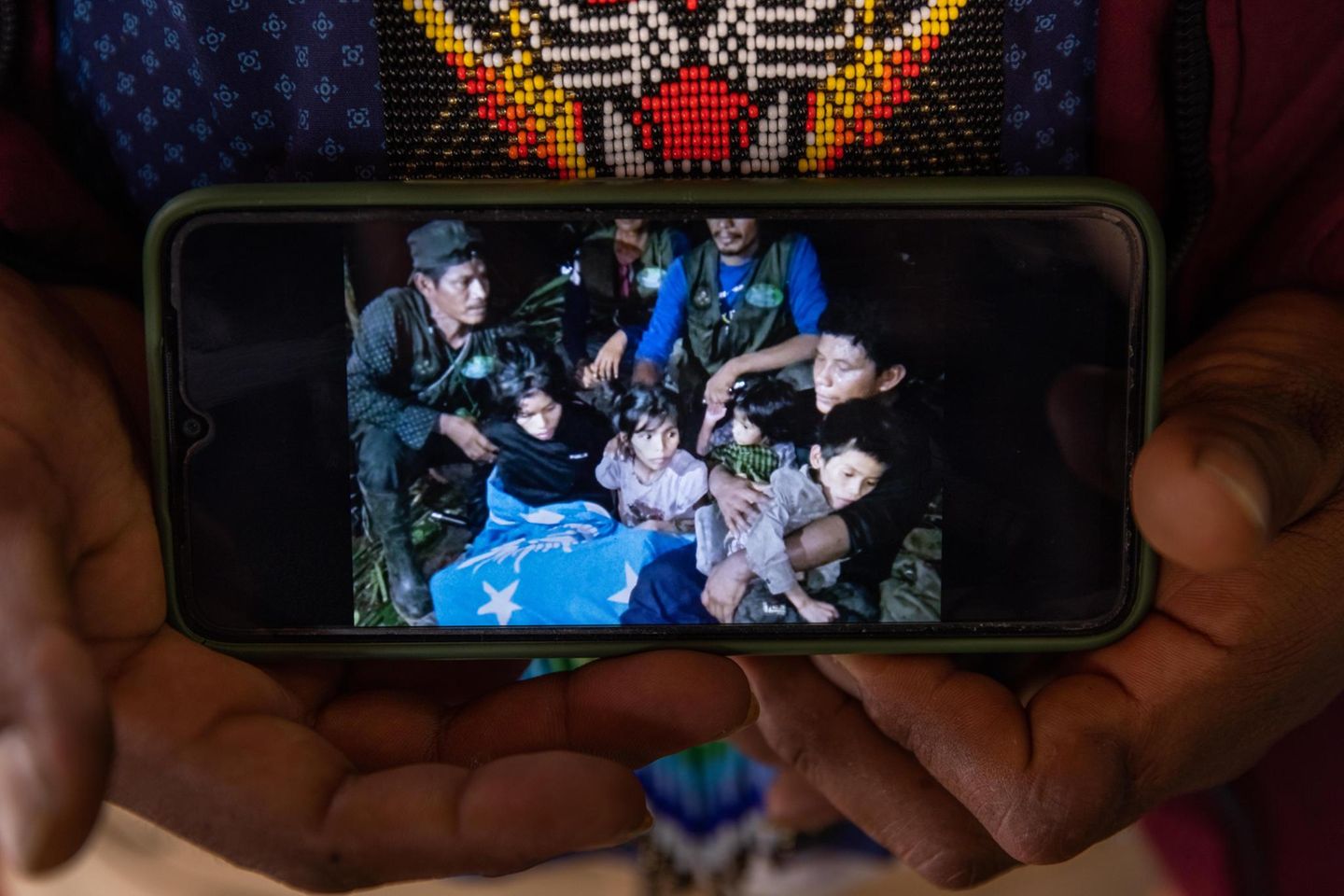

But then, on May 15, exactly two weeks after the crash, they pick up the first major clue: a pink baby bottle. Sánchez pulls out his cell phone and shows images of where it was found. It's the first glimmer of hope that some of the children may have survived the crash, maybe even all of them. He has the pictures sent to the children’s grandmother, Fátima Valencia. She confirms: The bottle belongs to little Cristin.

And then, that same evening, another breakthrough: Indigenous search teams, put together by the children's father, have discovered an aircraft wreckage around 8 p.m. But it's too dark to investigate it.

"That's it," Sánchez thinks.

***

The next morning, the general sends his top man to the crash site, Capitán Montiel who has been overseeing "Operation Hope" from the ground for the past ten days. He is an experienced soldier, 17 years in the military and familiar with everything. Or so he thought.

At dawn on May 16, he approaches the wreckage with six men. They can make out the outline only from 20 meters away, because the forest is so dense, and hardly a branch is damaged. "That's why we didn't spot it from the air," he explains later. The tail is intact. The engine ripped off. When he is only ten meters away, he notices the pungent smell of decaying corpses.

Montiel films everything and later shows the footage on the army computer to stern magazine. "Here you can see it: the bodies lying on top of each other. The pilot on top of the mother. No trace of the children at first. But it is clearly visible that the back seats are barely damaged."

Montiel searches the area. The aircraft door is open. The children apparently climbed over the dead mother to get out. Bags, clothes, and diapers are strewn around. Not far from the wreckage, Montiel and his men discover a camp. The children must have built it, with not much more than a few twigs, a towel and a mosquito net. "They survived the crash," he concludes. "But are they still alive? Possibly seriously injured? At least they grew up in the jungle, it’s in their blood."

Like almost every one of the 15 people stern magazine spoke with for this reconstruction of the events, Montiel's eyes, too, well up as he talks. He has two daughters, four and six, about the same age as the missing Tien. During the search, he can't stop thinking about them. "As a father, I always put myself in Manuel's shoes."

The interview with Capitán Montiel takes place at the Cantón Norte military base in Bogotá, where his elite unit is stationed. It is hermetically sealed off, like so much else in Colombia which like no other country has struggled with terrorism and attacks for the past 60 years.

The wreckage is now a crime scene, yet Montiel permits the father to access it. "I wanted to be sure," Ranoque says. His wife’s decomposed body, gnawed down to the bone by animals, a horrible sight. As if he needed to prove it, he pulls out his cell phone during the interview and shows pictures of his wife's body. Not much more than her long, wet hair is still recognizable. "The rainforest devours everything within a few days," he says.

How did you feel at that moment?

"It was very hard. She was a partner who sacrificed everything. But I had faith that I would find the children alive."

Tears well up in his eyes but he fights them back, as if embarrassed by them. "I just thought, where are my children? With all the trauma they have experienced. I didn't sleep, I didn't eat. But I didn't lose hope."

***

After the crash, Lesly unbuckles her seatbelt, climbs over the front seat, and wrenches her little sister Cristin from her mother's arms. She carries her out of the wreckage, and then helps Tien and Soleiny, as she will later tell her grandparents. She is bleeding from a head wound which she covers with one of Cristin's diapers.

Through interviews with Ranoque, the grandparents, and soldiers, stern magazine has pieced together an account of what happens next. The children initially stay at the crash site to protect their mother’s body but soon animals start attacking the corpse. The children decide to leave and not to return.

One can only guess how this horrible sight has damaged their souls. They will not talk about it in detail, not even with their family.

"What about Mom?" Tien asks his sister in the jungle.

"She's sleeping," says Lesly, who doesn't know if her brother understands that their mother is dead.

"When will she wake up?"

"I don't know."

Later, Tien will proudly tell his father, "I was the only one who didn't cry, Papa."

Lesly and Soleiny gather a few useful things from the wreckage: cassava flour, a pair of scissors, the baby bottle. Then they look for a water source. "That’s what they were taught at a young age," their father says. The stream eventually leads to a river, a village. "My own sister was once lost in the forest for 36 days before our shaman found her. The children know her story."

In a way, their life in the isolated jungle village of Puerto Zábalo, population 130, has prepared the children for times of adversity. There is no electricity, no cell phone service, no help from the state, the nearest road is six hours away, three by boat, three on foot. The families rely on the river for much of their food as well as the "chacra", an agricultural field for the entire community. They use forest plants to treat wounds and study the behavior of animals.

If anyone has the strength and will to survive, it would be Lesly. Her grandparents believe that, too. By the time she was 13, she cooked for the whole family and took care of her siblings while her parents worked. "She's very smart and responsible," Ranoque confirms. He is the stepfather to the two older girls; his biological children are Tien and Cristin. "But Lesly is not a survival expert as she has been portrayed in the media”, he says. She stayed mostly at home taking care of the little ones."

Tien is different from his shy sisters. He is talkative, feisty, but also more impatient. The girls need to keep calming him down. They take turns carrying little Cristin and preparing milk for her from the seeds of the Milpeso palm. By mid-May all four of them feel their strength slowly waning. Supplies are dwindling. Fruits are scarce.

"The hardest hit was not Cristin, but Tien". He was at greatest risk of starving to death, says Ranoque.

***

The news travels rapidly around the globe. June 16, 11:05 a.m. The indigenous children from the Amazon have survived the plane crash – a miracle. Their fate touches people all over the world, from Spain to China, Ukraine and Russia. A story of hope in dark times. A true fairy tale amid the oftentimes harsh realities. Can children survive alone in the jungle for that long? They have been missing for already two weeks.

Especially General Sánchez asks himself this question and does the math: After 16 days wandering the Amazon, they could be somewhere in an area the size of 60,000 soccer fields. In the densest jungle, visibility 20 meters, even less when it rains. To complicate things further, the children are constantly moving, which means the soldiers must repeatedly cover the same grids of the search area. He dispatches more units, 120 elite fighters in all.

Narciso Mucutuy, the children's grandfather, personally asks President Petro to send more indigenous people into the rainforest. They found the wreckage and know the jungle best, he argues; they can read tracks, interpret animal voices, challenge the forest spirit. Who, if not the indigenous people, can find the children?

300 kilometers from the crash site, in Putumayo, on the border with Peru, Eliecer Muñoz, 50, a simple farmer and member of the Guardia Indígena, a kind of indigenous security force, is also asking himself this question. He is close to the spiritual forces of the forest and has a feeling that his help could be important.

"You have no equipment," his wife says. "No boots, no pants."

"Don't go, Pupu," others say, calling him by his nickname. "You're too old."

But something is bubbling up inside the stocky man with alert eyes, a kind of foreboding. "Is it possible that I, of all people, will find them? I who has never had children of my own?" he wonders.

The president of the Guardia Indígena of Putumayo summons 25 men. The military provides a helicopter and is about to fly the volunteers into the search area, when at the last moment Elicier Muñoz appears and shouts, "Wait. Wait." and hops in.

Since he is the oldest, already 50, and knows the jungle, he is chosen to lead the group - and given an honorable name: Major. He sets only one condition: "We search alone without the military." He doesn't trust the soldiers. They have already committed too many massacres in Colombian history. There is too little understanding of indigenous spirituality. And that is what matters now, he is convinced.

The indigenous people around "Major" Muñoz don't use GPS or compasses. They don't study maps and satellite photos. On the eve of their search, they chew mambe, a mix of coco plant and yarumo tree leaves, and take ambil, a stimulating plant extract which they believe will help them receive spiritual guidance.

"Mambe gives us intelligence. Ambil gives us power," Muñoz explains later during the interview. "That's how we connect with the spirits of the forest."

He doesn't like the questioning look of stern magazine’s reporter. "You people in the West don't understand that", he says brusquely.

The conversation with him is not easy. He considers follow-up questions as criticism. "I talk to the forest, pay attention to signs, try to establish a connection. How else are we supposed to find the children."

The indigenous people of Putumayo comb the rainforest. Unlike the soldiers, they do not yell the children’s names. They do not cut down plants with machetes because that will only enrage Pachamama, Mother Earth. "You can send 2,000 men and you will never find the children if they are held captive by the spirits." Muñoz is sure of that.

Then, on May 16, they do find traces the soldiers missed. Scissors. Footprints. Fruit scraps. "We're getting closer," Muñoz believes. "But I sense a great deal of resistance."

***

Capitán Montiel reports the discovery of the clues to the operations center in Bogotá. There, General Sánchez meticulously records the findings and later shares his notes with stern magazine:

"Discovery hideout, scissors: 16 May 23, 10:00."

"Discovery footprints 1: 17 May 23. 16:45."

"Discovery footprints 2: 18 May 23. 11:12."

Sánchez is convinced they are close to finding the children. "You must search around the clock," he orders his soldiers. "Today we will find them."

He reports the progress to his superiors, the indigenous people report directly to the president, Gustavo Petro who will soon send out a fateful tweet: "After arduous searching by our military, we have found alive the four children who went missing after a plane crash."

The nation, it seems, has its happy ending, 17 days after the crash. The grandparents in Villavicencio are overjoyed. The children’s father Manuel Ranoque utters a prayer of thanks.

"What a mess," thinks General Sánchez.

Because the joy is premature. The message wrong. "We must have gotten within 100 meters," General Sánchez says. "The children surely heard us."

The president's tweet – a serious mistake?

"I really thought we had found them. We had proof. Footprints. But then everything changed."

Late on May 18, it starts to rain heavily. The downpour washes away every trace and footprint in the jungle. It will last for days and destroy all hope.

"Then I begged Mother Earth to answer our prayers." You prayed to the pachmama? Like the indigenous people do? "Yes, for the first time in my life. By that time, I had already prayed to the whole world – except to the devil, of course.

***

In Villavicencio, Fátima Valencia is devastated. It's an emotional roller coaster of hope and despair for the 52-year-old mother of Magdalena. "Everyone has forgotten about my deceased daughter. It was all about politics, about propaganda, about the military, supposed heroes."

Valencia is a small, slender woman with a cataract in her right eye and a weak heart. At a meeting with stern magazine at the presidential palace, she has nothing good to say about "Operation Hope." The great drama surrounding her family is supposed to heal the divided nation. But she is breaking up inside. She feels exploited.

Valencia finds it difficult to cope with the death of her daughter. She is hopeful that Magdalena’s spirit can live on in Lesly, who is so much like her mom. She describes her granddaughter as loving, kind to children, but also fierce. "A warrior."

During the search in the Amazon jungle, the grandmother's voice is used to comfort the children and ease their fears. Huge loudspeakers with a range of up to three kilometers broadcast her messages in the Witoto language, "I beg you, stay calm. The army is looking for you." Helicopters toss out more than 100 food boxes. The military marks eleven kilometers with bright yellow barrier tape and attaches whistles for the children to use them to call help. It deploys powerful searchlights for the nighttime search. And five sniffer dogs.

The young Belgian shepherd Wilson gets separated from his handler during the search but apparently finds the children and accompanies them for a few days. "And then he suddenly disappeared," Lesly will later say. Wilson remains missing.

"We really tried everything," says General Sánchez, who has seen it all during his 20 years in the Army, 15 of them at war. "This was my most difficult, most complicated mission."

The children are not afraid of the forest. Nor of the animals. "We saw a jaguar," Tien later tells his father. What they can't make sense of, on the other hand, is their grandmother's echoing voice in the middle of the jungle. Is she in the helicopter they can make out above the trees? They also hear other human voices but are afraid to approach them. Lesly fears being scolded for leaving the crash site, she will later tell her grandmother.

It is now June 26, little Cristin's first birthday. They are running out of food. This corner of the Amazon basin is considered "selva pobre," poor rainforest. Fruits and nuts are scarce here. Luckily, the children find one of the dropped food boxes - with cassava flour, cookies, water. The food lasts for a few days. But the little ones get a stomachache due to hunger.

The days pass, the hope of "Operation Hope" fades. All this modern technology only got them so far. "We need Don Rubio," Fátima Valencia has been saying for some time. If anyone could find the children, it would be the shaman.

Her son-in-law Manuel Ranoque agrees: "We need Don Rubio."

***

Jorge Rubio, 55, is a burly man with a stern look and a hot temper. Right at our first meeting in a hotel in Bogotá, he complains loudly that no one respects him and storms angrily out of the lobby. He throws away the military medal. "These things are meaningless for us indigenous people."

In the jungle, Jorge Rubio, known as "El Tigre," arrives on Day 23. The shaman from the Witoto people has twice before found people who had gone missing in the jungle, including Ranoque's disabled sister.

"I learned my visionary powers from my grandfather when I was ten years old. I started healing people when I was 15. The trees of the forest speak to me. They look at me. We are in constant contact," he says after he has calmed down.

In the search area, Don Rubio gets to work, but instead of combing the forest and looking for the children, he chews mambe for hours, takes Ambil, connects with the spirits of the rainforest. And reports his findings to the search parties: The children are alive. But they are in the grip of the Duendes, the forest spirits. They are in a hole in the ground. The Duendes will not release them.

And what do they eat?

"I send them spiritual food," he claims.

The explanation makes sense to the indigenous men on the search party. They all reckoned it was a struggle with higher powers. Don Rubio's words make less sense to the soldiers. Nevertheless, they send word to the Joint Special Operations Command.

To everyone's surprise, General Sánchez issues an order: "Team up with the indigenous people. From now on you work together, including with the seer and shaman Don Rubio. "I welcomed them into my battalion and said, "This is all for you, feel like kings." "I was criticized for that in the military: you're a soldier, a man of God, now you're changing sides," General Sánchez says. "But I'm indigenous myself, 80 percent of us have indigenous blood. If we have exhausted the military possibilities, then why don’t we try the spiritual ones?"

***

It is not Commander Montiel who sets off with the indigenous people, but his subordinate, Sergeant Rojas, who is particularly close to the indigenous people. It is already June, day 32 of the search operation, more than four weeks after the crash, and two weeks after the wreckage was found.

Rojas is a gentle giant, a 20-year veteran of the military, someone who is eager to learn from the indigenous people. The diverse rescue teams of army and indigenous people are beginning to complement each other. Food is supplied by Army helicopters, rice, cookies, beans, but the fresh fish are caught by the natives, one piranha after another. The strength of the military lies in its radio and GPS capabilities, the indigenous people know how to set up camps, and read tracks.

"They discovered tracks that we would never have found," Rojas admits.

Together they build shelters for the night, weaving roofs out of palm leaves. During the day, they set out together to continue the search. The soldiers even chew coca leaves with the indigenous people. Boundaries that existed for decades are dissolving.

"We have become friends," Don Rubio says. The soldiers, in turn, respectfully listen to the orders of "El Tigre." "We were under their command," Montiel confirms. "They communicate directly with Mother Earth. The forest speaks to them."

Still, they don’t find the children.

***

In desperation, the Joint Special Operations Command gives Capitán Montiel a mysterious order: "At midnight, we'll lower four bottles of liquor from the helicopter at the stream where it branches off. There, you'll get further instructions."

"I was thinking, what is that all about?" says Montiel. "We're elite troops."

The liquor is supposed to get the forest spirits drunk, he learns. The indigenous people have suggested it. The bottles are to be placed in all four cardinal directions.

"I felt like I was in a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm," Montiel recounts. "The GPS device suddenly failed with the pointer swinging wildly back and forth. Four of my men got lost in the jungle for three hours."

Sgt. Rojas adds, "Our shoelaces were suddenly tied together."

Magical Realism finds its way into the search for the children, like in a Gabriel García Márquez novel. General Sánchez later confirms, "Everyone got sick at the same time, chills, fevers, coughs, including Rojas and Montiel. The simple explanation: It was the humidity, the constant rain. Don Rubio's explanation: It was the dark forces of the jungle.

Two weeks after the search operation ended, General Sánchez still coughs throughout the interview. He says, "The rainforest is very mystical, there is a special energy." Even President Petro, in a speech that he will later give at the palace, will urge greater reliance on indigenous ancestral knowledge. "There is a magic that has a lot to do with this ancestral knowledge."

Even the well-equipped military lets itself be guided by indigenous visions. In fact, they provide the indigenous volunteers with the hallucinogenic narcotic yagé, also known as ayahuasca, so that they can summon their visionary powers. They see this as their very last chance.

***

On June 9, day 39 of the search operation, however, a feeling of disillusionment sets in. Many of the indigenous volunteers have given up. The army replaces weak and sick soldiers, including Montiel and Rojas. For 30 days they have marched 16 kilometers a day in sodden uniforms, lost eight kilos, didn’t shower once.

Major Muñoz, the leader of the group from Putumayo, feels a "deep sadness." "Maybe this is Mother Earth's revenge," he thinks. "She is taking revenge because we are cutting down the forests and stealing oil from the earth."

17 Indigenous people continue to search. And the children’s father, the only one there from the beginning, barely sleeps and eats.

"Hope was at its lowest point," Manuel Ranoque says. "So, I had to resort to extreme measures."

Shaman Don Rubio now prepares yagé. The potion is meant to put Ranoque in a trance. In the dream, he is supposed to find his children. "But Yagé is the ultima ratio, a very difficult experience."

Ranoque fails. "I was powerless against the forces. Against the animals. The jungle. I couldn't stand the pressure."

As a last resort, Rubio the shaman, decides to take Yagé himself. He offers the duende his own life in exchange for the children's. "I went into battle against the forest spirits, we wrestled, it went back and forth, but I kept the upper hand. And then I knew: tomorrow we will find the children. I told Eliecer: go that way, head west."

***

On June 10, Eliecer Muñoz sets off with three other indigenous people and as instructed by Rubio heads west. He encounters a large turtle that keeps tumbling down a small slope. "If you show me where the children are, I will let you live," he says. "If not, I will eat your liver." "And I'll drink your blood," adds Muñoz's companion, Dairo.

Major Muñoz straps the turtle on his back and continues walking up a steep hill. Soon they hear a baby crying between dense trees. Around 2 p.m. local time, they discover the children in a forest clearing. They are emaciated and exhausted. Lesly is holding little Cristin in her arms. Her sister Soleiny is standing next to her. Tien is sitting on the ground, a few steps away. He is nothing but skin and bones.

"We're hungry," Lesly says.

"My mother is dead," says Tien.

"Don't be afraid, your family sent us," Muñoz says.

He piggybacks Soleiny. The other indigenous men carry her three siblings. They are still a kilometer and a half to away from the camp, a two-hour walk. As promised, they release the turtle.

Completely exhausted, they reach the camp around 4 p.m. Manuel throws his arms around his children and won't let them go. He is sobbing. "They are nothing but skin and bones," he notes. "In two days, they would have been dead." The grandparents are informed by satellite, as is the president, the nation, the world.

"Milagro, Milagro, Milagro,".

Capitán Montiel weeps with joy. General Sánchez embraces his soldiers and the indigenous volunteers, "without whom we would still be searching." Don Rubio puffs tobacco smoke over the children to cleanse them. He cautions, "We the people must learn from this experience."

It is still dark when the military flies the children out to San José and on to Bogotá, the entire way accompanied by doctors and by Sergeant Rojas. He will later say: "The lesson for the world is this: It's not your religion that matters, it's not your race, it's not your skin color, it's that we take care of each other - and our world."

***

In late June, President Petro invites all participants of the rescue operation to his palace in the center of Bogotá. It is a clear, sunny day, the army orchestra is playing, a first documentary drama about the rescue operation is being shown on the big screen, the nation is celebrating itself. Petro awards the medals personally, to Sergeant Rojas, Capitán Montiel, the shaman Don Rubio, the rescuer Muñoz, to 86 heroes. The highest order is awarded to General Pedro Sánchez.

In his speech, the president evokes a "new Colombia" in which indigenous people and soldiers help each other, in which ancestral knowledge and Western science complement each other, in which Mother Earth is no longer exploited.

As is so often the case, a wonderful story becomes too loaded, with all kinds of symbolism and hyperboles, until it inevitably collapses under its own weight.

Besides Manuel Ranoque and Fátima Valencia, film agents and Hollywood representatives are in the audience. The battle over the marketing rights to this heroic epos has long begun. On behalf of the government and the military, the president quickly awarded the rights to award-winning director Simon Chinn. Producers sign contracts with Don Rubio, Muñoz, Ranoque and others. Some indigenous people sign three exclusive contracts at the same time. They pocket the money, a few thousand euros, disappear into the Amazon jungle and leave the Hollywood agents baffled. Their message is: Your contracts are meaningless to us. Just like your values.

At the same time, a custody battle for the four children has broken out. Magdalena Mucutuy's family accuses Manuel Ranoque not only of domestic violence, but also of abusing his stepdaughter Lesly.

Ranoque categorically denies the allegations. However, he admits to getting into physical altercations with his wife. "But only when I was drunk," he explains. "I just pushed her. We fought a lot."

Astrid Cáceres, head of the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare, the agency responsible for the children, says in an interview "We are taking our time to reach a decision. They are the children of Colombia now."

The children continue to recover. At first, they were hooked up to an IV, but soon started eating their beloved cassava flour again. Their father, grandmother, and aunts visit them every day at the military hospital, but the children don't talk much about the 40 days.

"It's the trauma," their father says.

Tien keeps asking him, "When will Mom be revived?"

"She's sleeping," his father replies. "One day we will see her again."

"I try to change the subject," he explains. "I read a lot to Tien. He likes fairy tales." Ranoque is convinced that his son experienced the greatest one himself.